| 0 Comments | Nzelum Cosmas

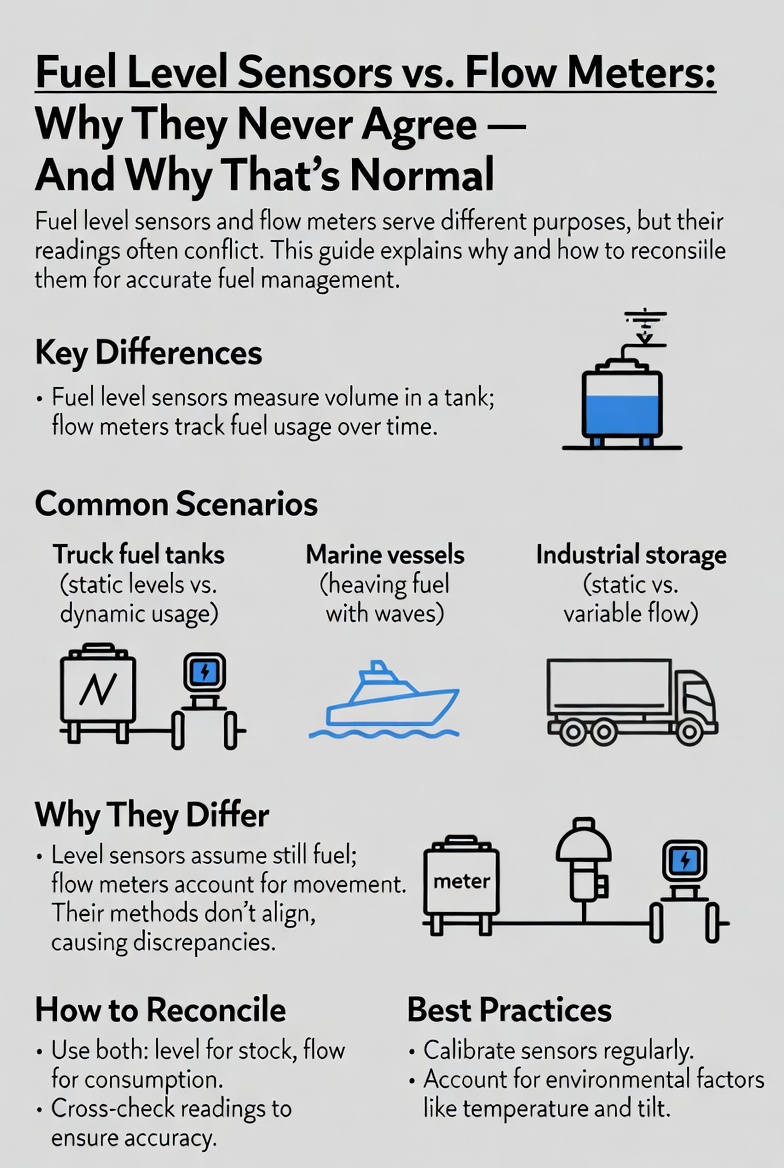

Fuel level sensors and fuel flow meters are both critical tools for monitoring fuel in various systems, but they serve fundamentally different purposes, which often leads to confusion about their readings, especially when both are connected to the same tank. This mismatch isn't due to a flaw in either device but stems from how they operate, what they measure, and the inherent limitations of each in real-world conditions. Below, I'll break this down step by step, starting with the core confusion and why exact alignment between the two isn't feasible, followed by an in-depth look at fuel level sensors (their usefulness, advantages, and wide usage), and then scenarios where flow meters shine.

Understanding the Confusion: Fuel Level Sensors vs. Flow Meters and Why Readings Don't Match Exactly

At a basic level:

- A fuel level sensor (e.g., float-type, capacitive, ultrasonic, or resistive) measures the static height or level of fuel in a tank. It typically outputs this as a percentage, volume (e.g., liters or gallons), or electrical signal to a gauge. It's like checking the water level in a glass—it's a snapshot of what's currently there.

- A fuel flow meter (e.g., turbine, positive displacement, or Coriolis type) measures the dynamic flow rate of fuel moving through a line, such as fuel being added to or removed from the tank. It quantifies volume per unit time (e.g., liters per minute) and can integrate this to give total volume transferred. It's like measuring how much water is pouring from a faucet.

The common confusion arises when people expect the change in fuel level (from the sensor) to perfectly match the volume recorded by the flow meter during filling, draining, or consumption. For instance, if a flow meter shows 50 liters of fuel added to a tank, users might assume the level sensor should immediately reflect an exact 50-liter increase—but it often doesn't, leading to perceptions of inaccuracy.

Why the Fuel Level Sensor Can't Read the Exact Value as the Flow Meter

Even when both are connected to the same tank (e.g., the flow meter on the inlet/outlet pipe and the level sensor inside the tank), discrepancies occur due to several physical, environmental, and design factors. These aren't errors but reflections of real-world complexities:

- Tank Geometry and Calibration Issues:

- Tanks aren't always perfectly cylindrical or uniform; many (like in vehicles or irregular storage tanks) have sloped bottoms, baffles, or non-linear shapes. A level sensor measures height, but volume isn't always proportional to height (e.g., in a tapered tank, 1 cm of height at the bottom holds less fuel than 1 cm at the top).

- Calibration drift: Level sensors are calibrated for a specific tank shape and fuel type, but if the tank deforms (e.g., due to pressure or age) or if the sensor isn't perfectly installed, readings skew. Flow meters, calibrated for linear flow, don't face this issue as they measure volume directly via mechanical or electromagnetic means.

- Scenario: In a truck's fuel tank during refueling, the flow meter at the pump accurately totals 100 liters added. However, if the tank is tilted (e.g., truck on a slope), the level sensor might read only a 95-liter increase because fuel pools unevenly.

- Environmental and Dynamic Factors:

- Temperature Effects: Fuel expands with heat (e.g., diesel expands by about 0.08% per °C). If fuel is added at a different temperature than what's already in the tank, the level sensor detects the combined volume, which might not match the flow meter's "cold" measurement. Flow meters can compensate for temperature if equipped, but basic ones don't.

- Sloshing and Movement: In mobile applications (e.g., vehicles, ships), fuel sloshes due to acceleration, braking, or waves, causing temporary level fluctuations. A level sensor might average readings over time, but during active flow, it can't instantly stabilize. Flow meters aren't affected by this since they measure inline flow, not tank contents.

- Vapor and Foam: During fast filling, air bubbles or foam form, artificially raising the perceived level temporarily. The level sensor picks this up as extra volume, while the flow meter only counts liquid fuel passed through it.

- Scenario: On a boat, a flow meter tracks fuel consumption to the engine (e.g., 20 liters used over an hour). Rough seas cause sloshing, so the level sensor shows erratic drops, averaging to only 18 liters less—leading to confusion about "missing" fuel.

- Sensor Precision and Resolution Limits:

- Level sensors have inherent inaccuracies (typically ±1-5% full scale), influenced by mechanical wear (e.g., float sticking), electrical noise, or resolution (e.g., a capacitive sensor might only detect changes in 0.5-liter increments). Flow meters are often more precise (±0.5% or better) for cumulative volume but can drift if not maintained (e.g., debris clogging a turbine).

- Integration errors: If the flow meter measures outflow but the level sensor doesn't account for evaporation, leaks, or minor spills, totals diverge over time.

- Scenario: In an industrial storage tank, a flow meter logs 500 liters dispensed. The level sensor, affected by sediment buildup at the bottom, shows a 510-liter drop because it misreads the initial level due to uneven settling.

- Measurement Principles and Timing:

- Level sensors provide indirect volume estimates (level → volume conversion via algorithms), while flow meters give direct volume. Any conversion error in the level sensor's software amplifies discrepancies.

- Timing lags: Level sensors update periodically (e.g., every few seconds), potentially missing rapid flows, whereas flow meters track in real-time.

In summary, the level sensor isn't "wrong"—it's just measuring a different aspect (static inventory) under variable conditions, while the flow meter tracks transactions. For exact reconciliation, systems often combine both with software corrections (e.g., in fleet management telematics), but perfect sync requires accounting for all variables, which is rarely practical without advanced calibration.

In-Depth Explanation: Usefulness, Advantages, and Wide Usage of Fuel Level Sensors

Fuel level sensors are indispensable for inventory management because they provide ongoing, at-a-glance awareness of fuel availability without needing to track every in/out flow. Their usefulness lies in enabling proactive decisions, preventing shortages, and integrating with automation.

Usefulness in Various Scenarios

- Real-Time Monitoring and Alerts: They allow continuous tracking of fuel levels, triggering alarms for low levels (e.g., in generators during power outages) or overflows during filling.

- Efficiency Optimization: By showing remaining fuel, they help plan refills, reduce downtime, and optimize routes (e.g., in logistics).

- Theft and Leak Detection: Sudden drops in level (unexplained by flow) can indicate leaks or unauthorized siphoning.

- Compliance and Reporting: In regulated industries, they log historical data for audits (e.g., environmental reporting on fuel storage).

- Scenario Example: In remote mining operations, sensors in diesel tanks monitor levels 24/7 via satellite telemetry. If levels drop below 20%, automated orders for refills prevent equipment shutdowns, saving thousands in lost productivity.

Advantages Over Alternatives (Like Flow Meters Alone)

- Cost-Effectiveness: Simpler design means lower installation and maintenance costs (e.g., a basic float sensor costs $200-400 vs. $800+ for a flow meter). No need for inline plumbing modifications.

- Simplicity and Reliability: Passive operation (no moving parts in some types like ultrasonic) makes them robust in harsh environments. They don't require power for measurement in mechanical variants.

- Non-Intrusive Integration: Easily retrofitted into existing tanks without disrupting flow lines. Compatible with digital systems for IoT connectivity.

- Versatility Across Fuels: Works with liquids like gasoline, diesel, kerosene, or even non-fuel fluids (e.g., water, chemicals), handling viscosities that might challenge flow meters.

- Energy Efficiency: Low power draw, ideal for battery-powered applications like remote sensors.

Despite limitations (e.g., sensitivity to tilt), advancements like digital compensation (using accelerometers for motion) have improved accuracy to ±0.5% in premium models.

Wide Usage Across Industries

Fuel level sensors are ubiquitous due to their adaptability:

- Automotive and Transportation: Standard in cars, trucks, and buses for dashboard gauges. In electric vehicles, similar tech monitors battery "fuel" levels. Fleet managers use GPS-integrated sensors to track fuel across hundreds of vehicles, reducing pilferage by 20-30% in some studies.

- Aviation and Aerospace: Critical for aircraft safety, where multi-sensor arrays (e.g., capacitive probes) ensure balanced fuel distribution across wings. Used in drones for mission planning.

- Marine and Offshore: In ships and oil rigs, they handle sloshing with baffled tanks and averaged readings, preventing engine failures at sea.

- Industrial and Energy: Storage tanks at refineries, power plants, and farms use them for bulk monitoring. In backup generators for hospitals/data centers, they ensure uninterrupted power during emergencies.

- Agriculture and Construction: Tractors and heavy machinery rely on them for fieldwork efficiency; sensors alert operators before fuel runs out in remote areas.

- Consumer and Residential: Home heating oil tanks or propane systems use them for automated reordering via apps.

- Global Scale: Billions are deployed worldwide, with the market projected to grow to $2.5 billion by 2028, driven by IoT and sustainability needs (e.g., optimizing fuel use to cut emissions).

Scenarios Where Flow Meters Are Applicable

Flow meters excel where precise measurement of movement (rate or total volume) is key, rather than static levels. They're ideal for transactional accuracy, process control, and efficiency analysis, often complementing level sensors.

- Fuel Dispensing and Retail: At gas stations, they ensure accurate billing (e.g., turbine meters measure pumped fuel to ±0.3% accuracy). In bulk transfers (e.g., tankers to storage), they verify deliveries against contracts.

- Engine and Machinery Consumption Monitoring: In vehicles or generators, they track fuel burn rate for performance tuning (e.g., detecting inefficient engines). Scenario: Fleet operators use them to calculate MPG, identifying underperforming trucks and saving 5-10% on fuel costs.

- Industrial Processes: In manufacturing, they control fuel injection in boilers or burners for precise energy input. In oil & gas pipelines, Coriolis meters handle high-pressure flows for custody transfer (legal billing).

- Research and Testing: Labs measure flow in engine prototypes to optimize designs. Scenario: Aerospace testing rigs use them to simulate fuel delivery under varying conditions, ensuring safety.

- Environmental and Compliance: Monitoring outflow in wastewater treatment (adapted for fuels) or emissions control. In marine bunkering, they prevent overfills and spills.

- High-Precision Applications: Where level sensors falter (e.g., very low flows or viscous fuels), flow meters provide data for predictive maintenance. Scenario: In aviation fueling trucks, they log exact amounts loaded onto planes, cross-checked with level sensors for redundancy.

In hybrid systems, combining both (e.g., flow for transactions, levels for inventory) resolves most confusions, providing a complete picture

0 comment(s) for "Fuel Level Sensors vs. Flow Meters: Why They Never Agree — And Why That’s Normal"

Leave a Reply